Imagine waking up one morning to find out you have 90 days to leave your country. Not because you committed a crime. Not because of war. But because your president had a dream—and in that dream, God told him you don’t belong.

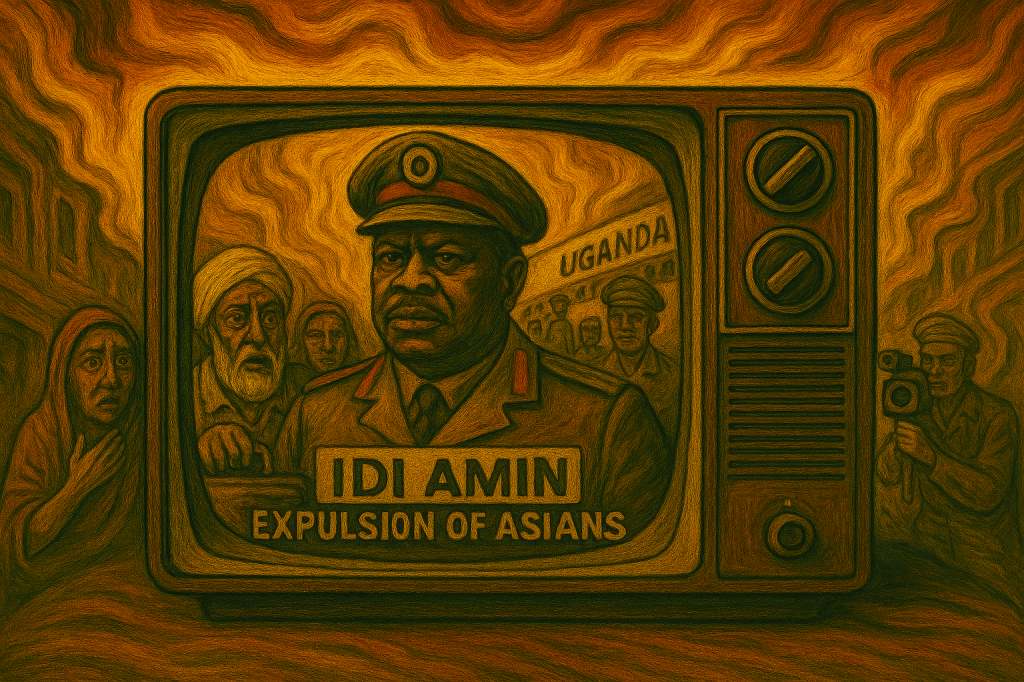

This isn’t fiction. In 1972, Idi Amin, the military dictator of Uganda, expelled over 70,000 Asians—mostly of Indian descent—from the country. They were told to leave everything behind: homes, businesses, memories. Many arrived in places like Leicester, Toronto, and yes, even Rotterdam. And while Amin’s regime is often remembered for its brutality, this particular act reveals something deeper: how colonial legacies, economic inequality, and identity politics can collide in ways that still echo today.

So why should we care? Because the story of Idi Amin isn’t just about Uganda. It’s about power, migration, and belonging. And if you’ve ever wondered what it means to “fit in” or who gets to call a place home, this story is for you.

Who Was Idi Amin?

Idi Amin Dada was born around 1923 in northwestern Uganda, in a region close to Sudan and Congo. He was part of the Kakwa ethnic group and raised mostly by his mother, a herbalist and spiritual healer. With little formal education, Amin joined the British colonial army—the King’s African Rifles—and quickly rose through the ranks thanks to his physical strength and loyalty.

In 1971, while President Milton Obote was abroad, Amin staged a military coup and declared himself president. At first, many Ugandans welcomed him. He released political prisoners, restored traditional kingdoms, and promised reform. But it didn’t take long before his rule turned into a nightmare.

The Expulsion: What Really Happened?

On August 4, 1972, Amin announced that all Asians had 90 days to leave Uganda. His justification? He claimed they were sabotaging the economy, exploiting black Ugandans, and refusing to integrate. He even said God had spoken to him in a dream, telling him to “give Uganda back to Ugandans.”

But the real reasons were more complex.

- Economic resentment: Asians controlled about 90% of Uganda’s businesses. Many black Ugandans felt excluded from economic power, and Amin tapped into that frustration.

- Colonial legacy: Under British rule, Asians had been placed in a middle position—above Africans but below Europeans. They were seen as outsiders, even after independence.

- Political distraction: Amin’s regime was unstable. By targeting a minority group, he diverted attention from internal problems and consolidated support among the masses.

Where Did They Go?

The expelled Asians scattered across the globe. About 28,000 went to the UK, where they were housed in temporary shelters before rebuilding their lives. Others went to Canada, India, the Netherlands, and even Sweden.

In Rotterdam, a small but resilient community formed. Families who had once run shops in Kampala now opened restaurants in Delfshaven or worked in logistics near the port. They brought with them stories of loss, but also of survival.

And here’s the thing: many of these families thrived. Within a generation, they built businesses, sent their kids to university, and became part of the social fabric of their new homes. Their story is one of forced migration—but also of remarkable resilience.

Amin’s Fall and Exile

Amin’s rule didn’t last. In 1979, after a failed invasion of Tanzania, his regime collapsed. He fled first to Libya, then to Saudi Arabia, where he lived in quiet exile until his death in 2003. He never expressed remorse. In fact, he insisted he had done what was best for Uganda.

Back home, the damage was deep. The economy had collapsed. Thousands had been killed. And the country was left to rebuild from the ruins of dictatorship.

Why This Still Matters

You might be thinking: okay, but what does this have to do with me, living in Rotterdam in 2025?

A lot, actually.

1. Migration and Belonging

In a city like Rotterdam, where over half the population has a migrant background, questions of identity are everywhere. Who gets to belong? Who is seen as “really Dutch”? The story of Uganda’s Asians reminds us how dangerous it is when belonging becomes conditional—when people are treated as guests in their own country.

2. Economic Inequality and Scapegoating

Amin blamed economic problems on a minority group. Sound familiar? In times of crisis, it’s easy to point fingers—at immigrants, at refugees, at anyone who seems “different.” But history shows us that scapegoating doesn’t solve problems. It just creates new ones.

3. Colonial Legacies

The tensions in Uganda didn’t start with Amin. They were rooted in colonial policies that divided people by race, class, and religion. And those legacies didn’t disappear with independence. They lingered—and exploded. In Europe, we’re still grappling with our own colonial past. Whether it’s debates about statues, reparations, or education, the ghosts of empire are still with us.

4. Pan-Africanism and Power

Some of Amin’s supporters saw him as a Pan-African hero—someone who stood up to the West and reclaimed African sovereignty. And yes, he did challenge neocolonial influence. But at what cost? Pan-Africanism, like any ideology, can be twisted. When it becomes a tool for exclusion or repression, it loses its soul.

Lessons for Today

So what can we learn from all this?

- History isn’t just in books. It’s in the streets of Rotterdam, in the families who fled Amin’s regime, in the debates we have about migration and identity.

- Power needs accountability. Amin ruled without checks. That’s how he got away with murder—literally. In any society, leaders must be held to account.

- Belonging is a right, not a privilege. Whether you’re born in Kampala or Katendrecht, your humanity shouldn’t be up for debate.

- Resilience is real. The expelled Asians didn’t just survive—they rebuilt. Their story is a testament to what people can achieve, even in the face of injustice.

Final Thoughts

Idi Amin’s Uganda was a tragedy. But it was also a mirror. It shows us what happens when fear overrides compassion, when power goes unchecked, and when history is ignored.

In Rotterdam, we have the chance to do better. To build a city where belonging isn’t about skin color or passport, but about shared humanity. To learn from the past—not repeat it.

So next time you walk past a South Asian restaurant in West, or hear someone talk about “echte Nederlanders,” remember Kampala. Remember the families who lost everything, and still found a way to thrive. And ask yourself: what kind of society do we want to be?

Because history isn’t just behind us. It’s in us.

Leave a comment