Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s polarizing former president, has just been sentenced to 27 years in prison for plotting a coup and inciting violence against democratic institutions. For young adults in Rotterdam—accustomed to stable governance, peaceful transitions of power, and a strong rule of law—this verdict feels both historic and unsettling. How can a democratically elected leader fall so far as to plan a takeover? And what lessons should we draw as citizens in the age of disinformation and political polarization?

From Populist Firebrand to Convicted Coup Plotter

Bolsonaro rose to fame by positioning himself as the anti-establishment candidate in 2018, promising to crack down on crime, curb corruption, and restore traditional values. His blunt rhetoric and savvy use of social media won him a solid following among conservative, rural, and evangelical voters. Yet after narrowly losing his bid for a second term in 2022, he refused to concede defeat, questioning the integrity of Brazil’s electronic voting system and urging his supporters to “take to the streets.”

Key charges against Bolsonaro include:

- Planning a coup to overturn the October 2022 election results.

- Leading a criminal organization made up of military officers and civilian operatives.

- Conspiring to assassinate President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and a Supreme Court justice.

- Coordinating the January 8, 2023 attacks on the National Congress, Presidential Palace, and Supreme Federal Court in Brasilia.

Prosecutors argued that Bolsonaro weaponized his presidential authority and personal network to undermine democracy. The Supreme Federal Court (STF) concluded that these actions posed a direct threat to the separation of powers, leaving judges no choice but to impose a heavy sentence.

Inside Brazil’s Judicial System

Many in Rotterdam may not fully grasp how Brazil’s legal framework works. Unlike the Netherlands, Brazil is a federal presidential republic with two houses of Congress and an activist high court that has increasingly asserted its independence.

– Chamber of Deputies: 513 members elected through open-list proportional representation, which encourages dozens of parties and coalition governments.

– Federal Senate: 81 senators (three per state), elected by plurality or majority vote in staggered terms.

– Supreme Federal Court (STF): Eleven justices appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. The STF can review and strike down legislation, prosecute high officials, and enforce constitutional rights.

In Bolsonaro’s case, a specially convened five-judge panel of the STF took evidence from phone records, financial transactions, and whistleblower testimonies. When four of the five judges voted to convict, they sent a clear signal: no political office, however high, guarantees immunity from criminal prosecution when it comes to attacking democratic order.

Brazil’s Deep-Rooted Party Fragmentation

Brazil’s parliament reflects profound social and ideological diversity, but it also suffers from chronic fragmentation. More than 30 parties hold seats in the Chamber of Deputies, making it hard to build stable governing coalitions.

– Open-list PR: Voters select individual candidates within party lists, giving personal popularity extra weight.

– Thresholds per state: Each of Brazil’s 27 federal units elects a fixed number of deputies, ranging from 8 to 70 seats, which distorts pure proportionality.

– Shifting alliances: Politicians often switch parties to improve their reelection chances or align with the ruling president.

This fractured landscape helped Bolsonaro ascend in 2018, as he united disparate conservative factions under a common banner. But it also left him politically isolated after 2020, when many centrist and moderate right-wing parties withdrew their support, weakening his ability to pass reforms and manage crises.

What the Verdict Reveals About Brazilian Society

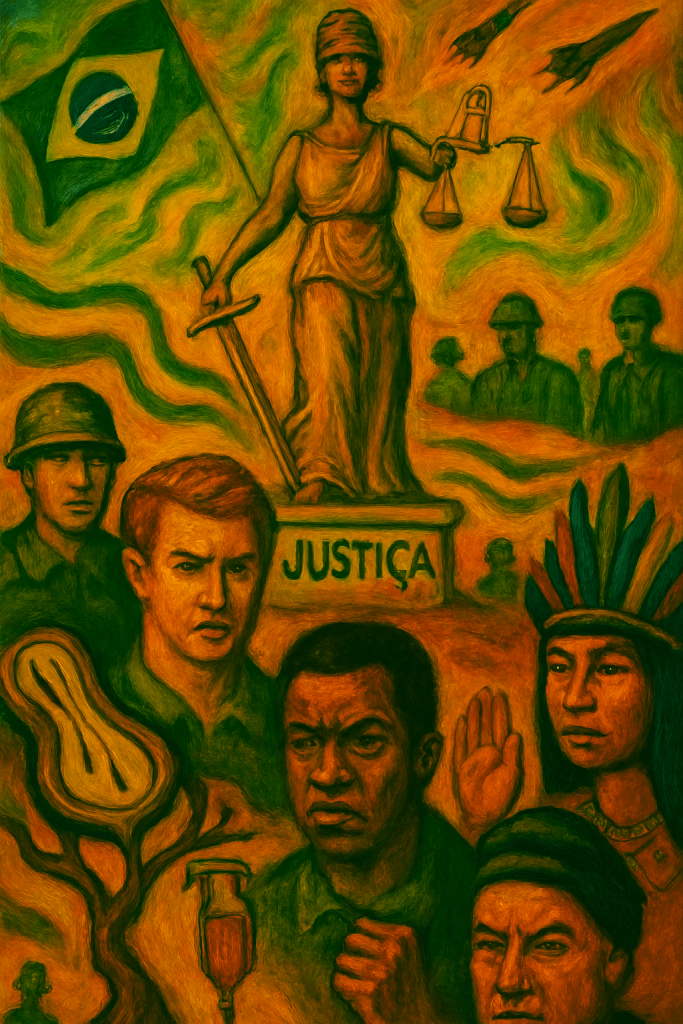

Bolsonaro’s downfall exposes deep contradictions within Brazil’s national identity. The myth of “racial democracy” glosses over stark inequalities based on race, class, and region. Religion—especially the rise of evangelical Protestantism—fuels both social conservatism and community networks, yet remains officially separate from the state.

– Race and class often intersect: Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous communities face disproportionate poverty and exclusion.

– Evangelical churches mobilized significant support for Bolsonaro, leveraging tight-knit congregations and alternative media channels.

– Militarism: Nostalgia for the 1964–1985 dictatorship endures among some segments that prioritize security and order over civil liberties.

The coup plot and subsequent conviction demonstrate that political grievances can quickly spill into extremist action when fueled by mistrust in institutions and social media echo chambers. The lesson for Rotterdamers is blunt: no democracy is immune to radicalization if citizens become disengaged or misinformed.

The Role of Disinformation and Social Media

Bolsonaro’s rise and fall went hand in hand with the spread of conspiracy theories on WhatsApp, Telegram, and Facebook. Unlike the traditional mainstream press, these encrypted platforms enabled fast, unchecked circulation of false claims about voter fraud, vaccine dangers, and sexual education programs.

Consequences of this digital firestorm include:

- Erosion of trust: Surveys reveal that a large segment of Brazilians believed the 2022 election was rigged, despite no evidence.

- Political polarization: Content algorithms favored sensationalist posts, strengthening divisions between left and right.

- Violent mobilization: Hyper-targeted messages convinced thousands to march on government buildings, convinced they were saving democracy from a “stolen election.”

For Rotterdam’s youth, accustomed to debating politics on Instagram and TikTok, this case underscores the perils of unchecked online discourse. Media literacy and critical fact-checking aren’t just academic buzzwords—they’re democratic necessities.

Reactions at Home and Abroad

After the STF verdict, jubilant crowds gathered in São Paulo and Salvador to celebrate what they saw as a victory for accountability and the rule of law. Opposition figures praised the court’s courage; human rights groups called it a moment of judicial reckoning.

Yet Bolsonaro’s supporters decried the sentence as politically motivated and vowed to pursue his release. Internationally, some populist leaders expressed solidarity, while most democratic governments hailed the decision as a sign that no ruler is above the law.

In Rotterdam, the news prompted reflection among Indonesian-Brazilian students, Afro-Latin cultural associations, and political science lectures at Erasmus University. It raised questions about how we safeguard elections, protect the judiciary from political pressure, and build resilient civic institutions.

Lessons for Young Rotterdamers

- Get informed: Follow multiple news sources and cross-verify contentious claims before sharing anything online.

- Engage locally: From neighborhood councils to climate protests, active citizenship strengthens community bonds and democratic health.

- Value independent courts: A judiciary that can check political power is as vital as free press and free speech.

- Understand electoral systems: The mechanics of voting—whether proportional, majority, or mixed—influence party dynamics and policy outcomes.

- Guard against echo chambers: Seek out people with differing views and treat social media skeptically.

By applying these takeaways, Rotterdam’s 20- to 30-year-olds can help ensure that our own democracy remains robust, inclusive, and peaceful—even when political passions run high.

What’s Next in Brazil

Bolsonaro has appealed to the full eleven-judge panel of the STF. His legal team argues procedural errors and questionable jurisdiction, but experts say a complete overturning of the verdict is unlikely. A more probable outcome is a slight reduction of his sentence or a protracted process that delays imprisonment.

Meanwhile, President Lula’s administration must navigate a deeply divided Congress, a recovering economy, and ongoing environmental crises in the Amazon. How Brazil reconciles its past and prevents future democratic backslides will depend on inclusive policies, transparent governance, and genuine social dialogue.

Conclusion

Bolsonaro’s 27-year conviction is a landmark moment—not just for Brazil, but for democracies worldwide. It proves that even the most powerful leaders can face consequences when they cross constitutional lines. For Rotterdam’s young adults, this saga is a stark reminder: democracy requires constant vigilance, informed participation, and respect for institutions.

Leave a comment