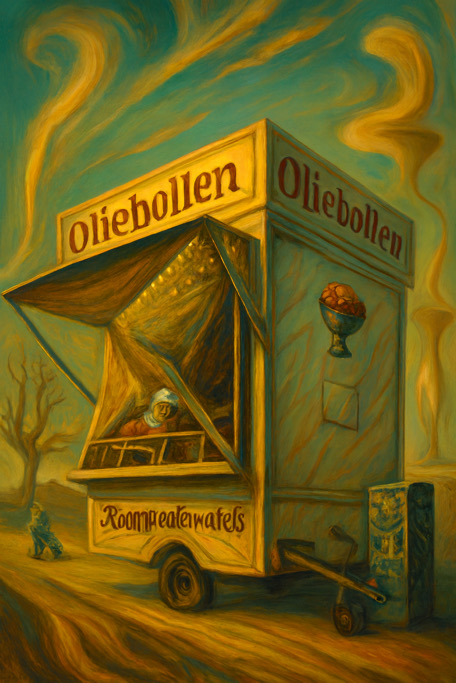

Rotterdam – It begins with a short walk through Crooswijk, the kind of walk that cuts your cheeks with cold air and makes your hands ache for warmth. At the corner where Crooswijksestraat meets Crooswijkseweg, there is a woman whose name I do not know, but whose face is as familiar as the bricks of the street. She bakes oliebollen — six for seven euros — and they are better than anything I could make myself.

This is not just about food. It is about ritual. About the comfort of returning home with a paper bag of steaming dough balls, sitting down with a cup of tea, and feeling that the winter is suddenly less cruel. In Rotterdam, these small gestures are the glue of community. They are the rhythm of the city, the heartbeat of the ordinary man in the street.

A Tradition Older Than the Streets

The oliebol is not a modern invention. Its roots stretch back into the mist of history. The Batavians and Frisians, early inhabitants of the Low Countries, already fried dough in oil during the darkest days of winter. They believed it offered protection against the goddess Perchta, who roamed the land in the cold season.

Later, in the Middle Ages, the oliekoek appeared — flat, heavy, fried in fat, eaten as sustenance at the end of fasting periods. It was cheap, filling, and durable. A food of survival, not luxury.

In the 17th century, when the Netherlands grew wealthy through trade, oil became more available. The dough rose higher, became rounder, and the oliebol as we know it was born. Sefardic Jews fleeing the Inquisition brought their own traditions of fried sweets, like sufganiyot, and these influences blended into the Dutch winter table. By the 19th century, the oliebol had become a fixture of New Year’s Eve, a symbol of nourishment and festivity.

The Purity of a Custom

Unlike other traditions, the oliebol has remained untouched by controversy. No protests, no debates, no accusations. It is a tradition that has survived the centuries without being weaponized. It is pure, simple, and shared.

In a time when Sinterklaas has been torn apart by arguments over Zwarte Piet, when midwinter fires have been extinguished by police intervention, the oliebol stands as a survivor. It carries the weight of history — Batavian, Frisian, Jewish, Dutch — and yet it is free of “gezeur,” free of noise.

This is why it matters. Because in the midst of shifting demographics, political disputes, and cultural battles, there is still one ritual that belongs to everyone. A bag of oliebollen is not a symbol of division. It is a symbol of continuity.

Fires That Once Lit the Streets

But not all traditions have survived so peacefully. As a child and teenager, I joined the neighborhood youth in collecting discarded Christmas trees. We fought over them, dragged them through the streets, and piled them high for the great bonfire of New Year’s Eve. It was a ritual of light, of destruction and renewal.

These fires were not just entertainment. They were echoes of ancient Germanic midwinter festivals, where flames were lit to call back the sun and burn away the old year. They were communal acts, binding the youth together in sweat, rivalry, and triumph.

Today, they are gone. Authorities have banned them, citing safety and environmental concerns. Police intervene when young people try to revive them. What was once a living tradition has been reduced to memory.

The Changing Face of the City

It is easy to blame this disappearance on rules and regulations. But there is another layer: the changing composition of the city. Rotterdam is no longer dominated by a single majority. The “blanke Hollandse” youth who once filled the streets with bonfires are now part of a more diverse mosaic. Traditions shift, adapt, or fade as communities change.

This is not a judgment, but a reality. Cities evolve. Customs that once defined a neighborhood may no longer resonate with its new inhabitants. The bonfires of Crooswijk were once a symbol of belonging. Now they are relics, remembered by those who lived them, invisible to those who did not.

Sinterklaas and the Burden of History

The Sinterklaas feast is another example of a tradition reshaped by time and conflict. Its roots lie in Wodan, the Germanic god who rode his eight-legged horse Sleipnir across the skies, accompanied by two black ravens. He visited children during midwinter, leaving gifts and sweets.

With the spread of Christianity, Wodan became Saint Nicholas, the bishop of Myra, known for his generosity. In the Netherlands, he was celebrated on December 5th, bringing gifts to children.

In colonial times, Zwarte Piet was added to the story, a servant figure whose presence reflected the racial hierarchies of the era. For decades, Piet was accepted without question. But in the past ten years, the debate has exploded. Accusations of racism, defenses of tradition, protests, and counter-protests have turned a children’s feast into a battlefield.

For many, this has been heartbreaking. A celebration of innocence has been consumed by conflict. What was once a source of joy has become a source of pain.

The Oliebol as a Survivor

And yet, through all this, the oliebol remains untouched. No one argues about its origins. No one protests its symbolism. The Batavian and Frisian myths, the Jewish influences, the Dutch adaptations — all are accepted as part of its story.

It is a tradition that has survived the centuries without being politicized. It is a ritual that belongs to everyone, regardless of background. It is a taste of the past that still warms the present.

When I walk to Crooswijksestraat and buy six oliebollen for seven euros, I am not just buying food. I am participating in a ritual that connects me to the Batavians, the Frisians, the Jews, the Dutch. I am tasting history. I am tasting continuity.

The Energy of the Street

This is what Rotterdam is about. Not grand monuments or official ceremonies, but the small rituals of the street. The oliebollen vendor on the corner. The bonfires that once lit the night. The children waiting for Sinterklaas.

It is the energy of the ordinary man, the rhythm of the neighborhood, the heartbeat of the city. It is the passion for life, the fury against poverty and oppression, the idealism for a better world. It is the young spirit that refuses to be crushed, the lust for freedom that burns even in the coldest winter.

A Tradition That Belongs to Everyone

For new arrivals in the Netherlands, for those who speak English but not yet Dutch, the oliebol is a perfect introduction to the culture. It is simple, accessible, and universal. It requires no explanation, no translation. It is a taste of belonging.

For those outside the Netherlands, considering a future here, the oliebol is a symbol of what survives. A tradition that has endured centuries of change, untouched by controversy, still alive in the streets of Rotterdam.

Conclusion: The Pure Flame of Continuity

Traditions rise and fall. Bonfires are extinguished. Sinterklaas is torn apart by debate. But the oliebol remains. It is the pure flame of continuity, the survivor of centuries, the taste of winter that belongs to everyone.

In Crooswijk, at the corner of Crooswijksestraat and Crooswijkseweg, a woman bakes oliebollen. I do not know her name. But I know her face, and I know the warmth of her food.

That is enough. That is Rotterdam. That is history alive in the present.

Leave a comment