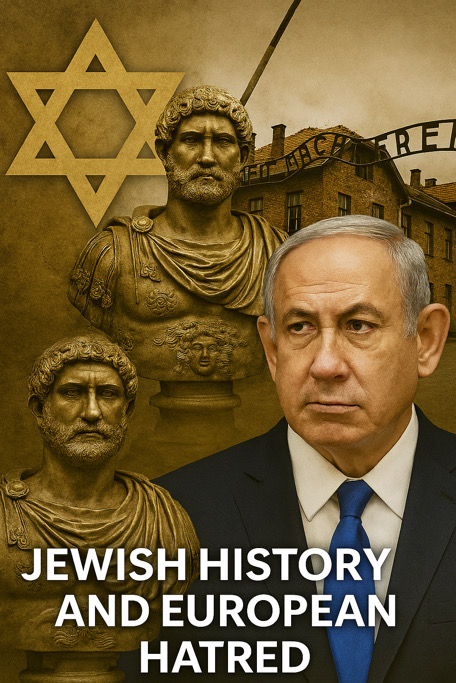

I. Hadrian and Religious Suppression

Emperor Hadrian (76–138 CE), known as the “travelling emperor” of the Roman Empire, left a lasting mark on both Western Europe and the Middle East. During his reign, he visited the northwestern provinces of the empire, including Germania Inferior—modern-day Netherlands and Belgium. Cities like Forum Hadriani (now Voorburg) and Ulpia Noviomagus (now Nijmegen) bore his name and influence.

But Hadrian’s legacy in Judea was far more devastating. Following Jewish revolts, he banned circumcision and rebuilt Jerusalem as a Roman city named Aelia Capitolina. Jewish religious practices were criminalized, and thousands were expelled or enslaved. This marked one of the earliest examples of state-sponsored antisemitism—not merely religious intolerance, but a systematic attempt to erase a culture.

II. The Middle Ages: Church-Sanctioned Hatred

In medieval Europe, antisemitism became deeply embedded in Christian theology and policy. The Catholic Church propagated the belief that Jews were responsible for the death of Christ—a narrative that fueled centuries of persecution.

Institutional measures followed:

- Fourth Lateran Council (1215): Jews were forced to wear distinctive clothing

- Ghettoization: Jews were confined to segregated neighborhoods

- Occupational bans: Jews were excluded from guilds and many professions

- Blood libel and host desecration accusations: These myths often incited violent pogroms

Jewish communities in cities like Mainz, Worms, and Speyer flourished culturally but lived under constant threat. Church authorities legitimized antisemitic policies, embedding hatred into the very structure of European governance.

III. The Sephardic Diaspora: Tolerance and Segregation

After their expulsion from Spain and Portugal in the 15th century, many Sephardic Jews found refuge in Amsterdam. The city, known for its relative religious tolerance, became a sanctuary where Jews could practice their faith openly.

Amsterdam blossomed into a hub of Jewish life:

- The Portuguese Synagogue was built in 1675

- Thinkers like Baruch Spinoza influenced European philosophy

- Jewish communities thrived in trade, diamond cutting, and printing

Yet tolerance had its limits. Jews were barred from public office and political influence, and often lived in separate districts. Later, Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe joined the Sephardic community, enriching Amsterdam’s Jewish culture while maintaining social divisions.

IV. Emancipation and Shifting Narratives

The Enlightenment and the French Revolution ushered in a new era. In 1796, Jews in the Netherlands were granted full civil rights, marking a turning point in their integration into European society.

This led to a period of flourishing:

- Jews became doctors, lawyers, scientists, and politicians

- Figures like Tobias Asser and Lodewijk Visser emerged as prominent leaders

- Jewish schools, newspapers, and cultural organizations were established

However, the nature of antisemitism began to shift. No longer rooted solely in religion, it evolved into racial and economic prejudice. Jews were accused not of heresy, but of being “foreign” and of manipulating the economy. Pseudoscientific theories about race and heredity fueled this modern antisemitism.

V. The Holocaust: Antisemitism as State Ideology

The 20th century brought both technological progress and the darkest chapter in Jewish history: the Holocaust. Across Germany, Austria, Poland, and the Netherlands, Jews were systematically persecuted and murdered.

In the Netherlands:

- Jews were registered and isolated

- Forced to wear the yellow Star of David

- Deported via Westerbork transit camp to Auschwitz and Sobibor

Of the approximately 140,000 Jews in the Netherlands, over 100,000 were murdered—the highest percentage in Western Europe. The Holocaust was not only a German atrocity but also a Dutch tragedy, enabled by collaboration, bureaucracy, and societal indifference.

Antisemitism had become more than a social prejudice—it was a state ideology, enforced through laws, propaganda, and industrialized violence.

VI. Post-War Silence, Recovery, and Remembrance

After 1945, survivors returned to looted homes, an indifferent government, and a society eager to move forward. Only in the 1960s and 1970s did Holocaust awareness begin to grow, with memorials, education programs, and public commemorations.

Yet antisemitism persisted—sometimes hidden, sometimes in new forms. The narrative shifted again: from religion and race to politics and conspiracy.

VII. The New Antisemitism: Bankers, Reptilians, and Israel

In the 21st century, antisemitism has morphed into digital-age conspiracy theories. Jews are no longer accused of medieval crimes but of global control through banking, media, and technology.

One of the most bizarre and persistent myths is that of the “reptilians”—a theory popularized by David Icke, claiming that world leaders (often with Jewish backgrounds) are shape-shifting aliens manipulating humanity. This sci-fi fantasy blends seamlessly with antisemitic tropes about secret elites.

The image of the Jewish banker, often represented by the Rothschild family, is used to channel economic anxiety and social frustration. In these narratives, Jews are not individuals but symbols of power and manipulation.

Additionally, anti-Zionism sometimes crosses into antisemitism. While criticism of Israel’s policies is legitimate, holding all Jews collectively responsible for the actions of a state blurs the line between political critique and hate.

VIII. Conclusion: Hatred Is Futile

What can we learn from this long history—from Hadrian to reptilians?

That hatred is futile. It destroys lives, communities, and societies. It consumes energy, time, and humanity. And it yields nothing but fear, division, and violence.

If children no longer learn this in school, we must teach it ourselves—through platforms like Dutch Echo, through kitchen-table conversations, through art, music, and education.

The lesson of Jewish history is not just about a minority—it’s about all of us.

Let us not only remember, but understand. Not only acknowledge, but act. Because only then can we build a society where wisdom is stronger than madness, and humanity triumphs over myth.

Middle-East

Leave a comment