You’re walking through Crooswijk, hoodie up, earbuds in. The city’s buzzing, but your mind’s somewhere else. Then Voodoo Child (Slight Return) kicks in. That first riff? It doesn’t ask for permission—it hijacks your mood. Suddenly, you’re not just listening. You’re feeling. And that’s the thing about Jimi Hendrix: he didn’t just play music. He channeled something. Something raw, rebellious, and real.

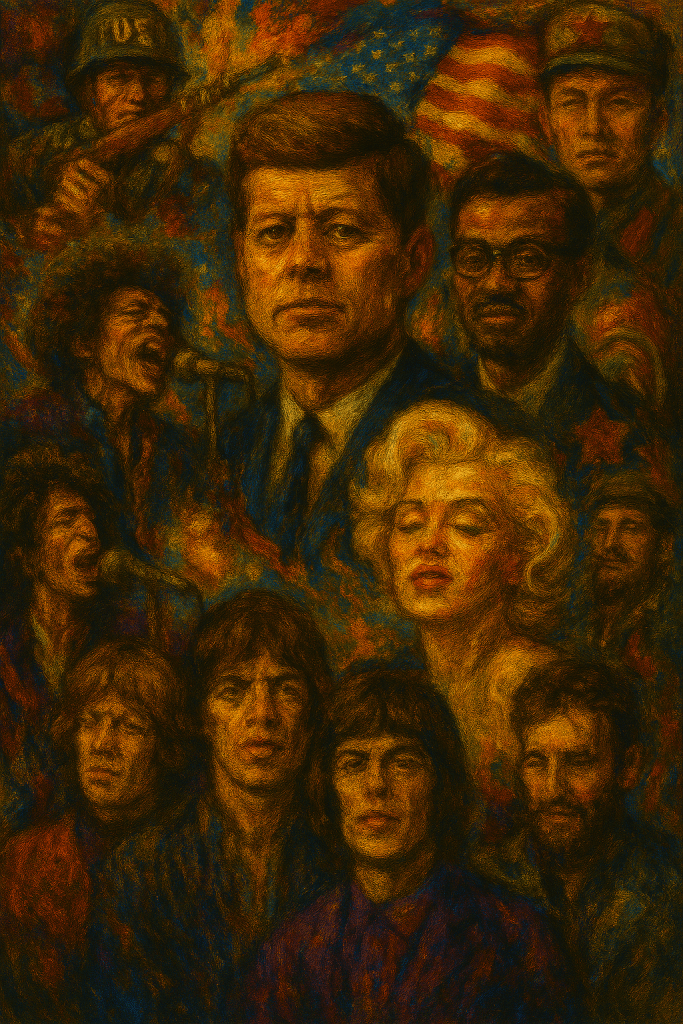

This essay isn’t just about Hendrix the guitar god. It’s about Hendrix the symbol. Of protest. Of identity. Of creative freedom. And yeah, of chaos too. Because if you’re in your 20s or 30s in Rotterdam right now, navigating identity, politics, culture, and connection, Hendrix still speaks your language—even if he’s been gone for over 50 years.

Born Into Noise, Raised Into Sound

Jimi Hendrix was born in Seattle, Washington, in 1942, as Johnny Allen Hendrix. His childhood? Messy. Poverty, instability, and a complicated family life. His father renamed him James Marshall Hendrix, and by the time he was a teenager, he was already obsessed with music. Not with fame. With sound.

At 13, he got his first guitar. At 17, he was playing in local bands. By 23, he was in London forming The Jimi Hendrix Experience. And from there, it was like the universe cracked open. Hendrix didn’t just enter the scene—he redefined it.

Hendrix and the Baby Boomers: The Soundtrack of Rebellion

Our parents’ generation—the so-called baby boomers—grew up in the shadow of war, in the middle of social revolutions, and in the rise of counterculture. Hendrix was their soundtrack. Not just because he was good (he was insanely good), but because he represented something they were craving: freedom, expression, and resistance.

Take Woodstock 1969. Hendrix played The Star-Spangled Banner like it was a siren. His guitar mimicked bombs, screams, and chaos. It wasn’t just a performance—it was a protest. Against Vietnam. Against conformity. Against silence.

For hippies, he was a spiritual guide. For Black youth, a pioneer. For the establishment? A threat. And for the youth? A legend.

A Black Man in a White Rock World

Let’s not sugarcoat it: Hendrix was a Black artist in a white-dominated rock scene. He broke through, but it wasn’t easy. He was often exoticized, mystified, even dehumanized. People couldn’t believe his talent was real. So they made him into a myth.

But Hendrix was real. And his roots were complex—Afro-American, Cherokee, Irish. His music reflected that mix: blues, soul, psychedelia, rock. He wasn’t a genre. He was a universe.

In today’s Rotterdam, where conversations about race, identity, and representation are still urgent, Hendrix reminds us: talent doesn’t have a color. But color still shapes how talent is treated.

Style as Protest: Hendrix’s Visual Power

Look at Hendrix’s outfits. Velvet jackets, wild prints, scarves, afros. He didn’t dress to impress. He dressed to express. His style was loud, unapologetic, and political. In a world that tried to shrink him, he made himself larger than life.

His performances were visual rituals. Take Live in Maui, 1970—no fancy stage, no pyrotechnics. Just amps, nature, and raw energy. It was spiritual. Psychedelic. Almost ancestral.

For creatives in Rotterdam—filmmakers, designers, musicians—this is gold. Hendrix shows us that image and sound together can tell stories deeper than words. He’s proof that aesthetic is activism.

What Hendrix Means to Us Now

We live in a time of fast takes, viral outrage, and curated identities. Activism is often digital. Identity is often performative. And that’s not a diss—it’s just the reality. But sometimes, we miss the messiness. The vulnerability. The imperfection.

Hendrix wasn’t a polished activist. He was a searching soul. And that’s why he still matters. His music invites us to feel. To reflect. To create. Not for clout, but for truth.

In Rotterdam—especially in places like Delfshaven and Crooswijk—where cultures collide and generations clash, Hendrix is a bridge. Between past and present. Between protest and poetry.

A Visual Essay: Hendrix as Lens

Imagine this: a visual essay that uses Hendrix as a lens to explore Rotterdam today. Young people finding their voice. Elders passing down stories. The tension. The tenderness.

We could blend footage of Hendrix’s performances with shots of our city—graffiti walls, street fashion, spoken word nights, protests, quiet moments. His riffs as soundtrack. His style as inspiration.

Because Hendrix isn’t just history. He’s alive in every creative act that refuses to be silenced.

Hendrix and the Power of Sound

Let’s talk about the music itself. Hendrix didn’t just play guitar—he bent time. He used distortion, feedback, and wah-wah pedals like paintbrushes. His solos weren’t technical exercises. They were emotional outbursts.

He made sound feel like memory. Like protest. Like prayer.

And that’s something we need now. In a world of algorithmic playlists and AI-generated beats, Hendrix reminds us that music can still be human. Messy. Spiritual. Political.

From Rotterdam to the World: Why This Matters

DutchEcho isn’t just a platform. It’s a space for reflection, connection, and critique. And Hendrix fits right in. His story isn’t just American. It’s universal. It’s about finding your voice in a world that wants you quiet.

For young adults in Rotterdam—navigating identity, culture, politics, and creativity—Hendrix is a reminder that rebellion can be beautiful. That style can be substance. That sound can be sanctuary.

Final Thoughts: An Invitation

This essay isn’t a conclusion. It’s a beginning. A call to listen deeper. To create louder. To connect across generations and cultures.

So grab your camera. Write that verse. Sample that riff. Make that collage. And let Hendrix guide you.

Because as he once said:

“When the power of love overcomes the love of power, the world will know peace.”

And maybe, just maybe, that peace starts with a guitar, a story, and a city that dares to feel.

Leave a comment