Rotterdam – On Sunday, December 7, 2025, the small West African nation of Benin found itself at the center of a storm. A group of soldiers appeared on state television, announcing that President Patrice Talon had been removed, the constitution suspended, and the borders closed. For a few tense hours, the country seemed to teeter on the edge of chaos. By Monday morning, however, the government declared the coup had failed. Talon was safe, and the streets of Cotonou and Porto-Novo were once again under heavy military control.

This story may feel distant from Rotterdam, but it speaks volumes about the fragile balance of power in West Africa, the lingering shadow of colonial influence, and the way global politics ripple through local lives. To understand what happened in Benin, and why it matters, we need to look at the players involved, the history that shaped them, and the broader regional context.

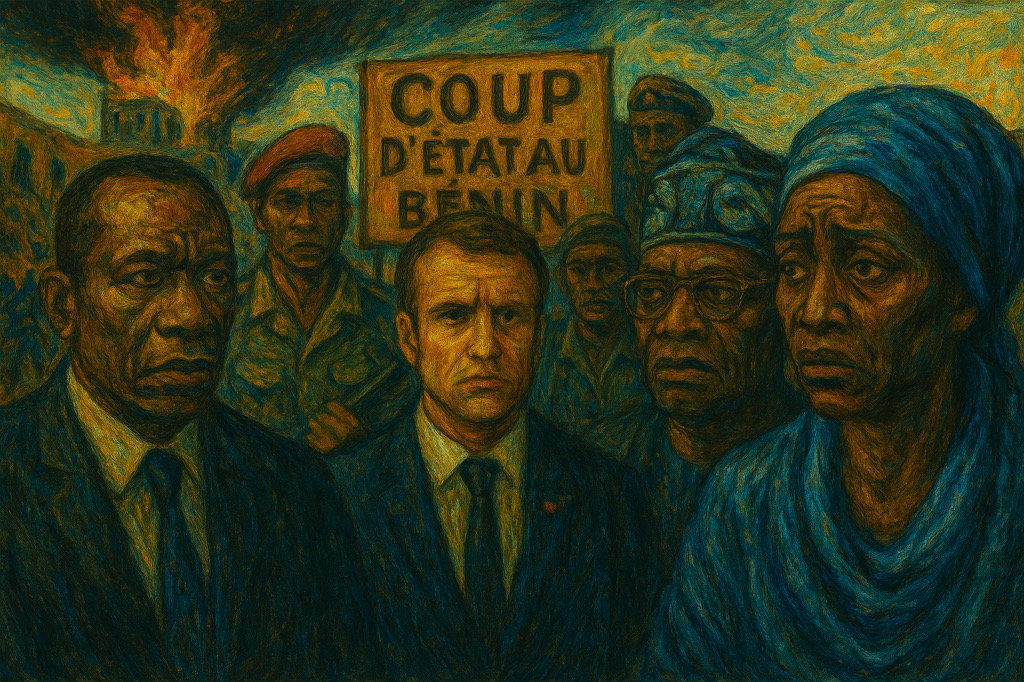

The Coup That Failed

The group behind the attempted takeover called itself the Military Committee for Refoundation (CMR). Led by Lieutenant Colonel Pascal Tigri, a former member of Talon’s personal security detail, they tried to storm the presidential residence and seize control of the state broadcaster. Their televised declaration was short-lived. Within hours, Interior Minister Alassane Seidou announced that the coup had been crushed.

Reports confirmed violent clashes in the capital, with several deaths and at least fourteen arrests. Some of the coup leaders remain at large, but the government insists the situation is under control. Talon himself was evacuated with the help of the French embassy, a reminder of the enduring ties between Benin and its former colonial ruler.

France’s Long Shadow

Benin, once known as Dahomey, was colonized by France in the late 19th century. Independence came in 1960, but the French presence never truly disappeared. The official language remains French, and Benin is a member of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie. Economically, the country has long relied on French aid and investment.

In the days following the coup attempt, France played a visible role. The French embassy provided shelter and security for Talon, while Paris issued a statement condemning the coup and calling for respect of constitutional order. For critics, this was another example of “Françafrique,” the enduring influence of France in its former colonies. For supporters, it was proof that France remains a stabilizing force in a region increasingly marked by instability.

Nigeria Steps In

Perhaps the most striking development was Nigeria’s rapid intervention. Within hours of the coup announcement, Nigerian fighter jets were patrolling Benin’s skies, and troops were deployed to secure key sites. Nigeria’s president, Bola Tinubu, made it clear that his country would not tolerate instability on its western border.

This intervention highlights Nigeria’s dual identity: a nation struggling with its own internal security challenges, particularly against Boko Haram and ISWAP in the northeast, yet also a regional heavyweight capable of projecting power beyond its borders. For Nigeria, Benin is more than a neighbor. It is a vital trade partner, a gateway to the Atlantic, and a buffer against the spread of extremist violence.

The paradox is clear. Nigeria struggles to protect its own citizens from insurgent attacks, yet it can mobilize quickly to defend a neighboring government. This contradiction has fueled criticism at home, but it also underscores Nigeria’s determination to assert itself as West Africa’s leader.

The Regional Pattern

Benin’s coup attempt did not happen in isolation. In recent years, West Africa has been rocked by a wave of military takeovers. Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have all seen their governments toppled by soldiers. These regimes often frame themselves as anti-French, turning instead to Russia for military support.

This “coup belt” stretching across the Sahel reflects deep frustrations with corruption, insecurity, and foreign influence. Extremist groups exploit weak states, while populations grow disillusioned with democratic promises that fail to deliver. Against this backdrop, Benin had been seen as relatively stable. The failed coup challenges that perception and raises questions about whether the instability is spreading southward.

Russia and China: Silent Observers

Unlike France and Nigeria, Russia and China have remained silent on the events in Benin. Moscow has built strong ties with military regimes in Mali and Burkina Faso, often through private military contractors. Beijing, meanwhile, invests heavily in infrastructure across Africa but avoids direct involvement in political crises.

Their silence in Benin suggests that the country is not yet a priority in their strategic calculations. Still, the broader trend is clear: as France’s influence wanes in parts of West Africa, Russia and China are waiting in the wings, ready to expand their reach.

What This Means for Europe

For Europe, and for the Netherlands in particular, the events in Benin are more than a distant headline. West Africa is a region deeply connected to Europe through trade, migration, and history. Instability there can ripple outward, affecting shipping routes, economic partnerships, and humanitarian concerns.

The euro itself remains stable, but the CFA franc — a currency used in many francophone African countries and pegged to the euro — could face pressure if coups and instability continue. The planned transition to a regional currency, the ECO, may be delayed further. For European policymakers, the challenge is balancing support for stability with respect for African sovereignty.

The Dutch Perspective

From Rotterdam, the story of Benin resonates in subtle ways. The city’s port is a hub for global trade, including goods from West Africa. The Dutch tradition of critical engagement with global events means that what happens in Cotonou is not just “their problem.” It is part of a shared world where colonial history, economic ties, and cultural connections continue to shape the present.

Dutch Echo’s readers know that history is not a distant memory. The colonial past informs today’s geopolitics, and the choices made in Paris, Abuja, or Porto-Novo can echo in Amsterdam, The Hague, and Rotterdam. The failed coup in Benin is a reminder that stability is fragile, and that the narratives of power, resistance, and influence are constantly being rewritten.

Scenarios Ahead

Looking forward, three possible scenarios emerge:

- Stable Government: Talon’s administration consolidates power, arrests remaining coup leaders, and restores confidence.

- Fragile Stability: Sporadic unrest continues, with lingering threats from disgruntled soldiers or extremist groups.

- Escalation: If unrest spreads or external actors intervene, Benin could slide into deeper instability, though a full-scale civil war seems unlikely at present.

For now, the first scenario appears most likely. The government has reasserted control, and international support has reinforced its position. But the fragility of the situation cannot be ignored.

Conclusion

The failed coup in Benin is a story of resilience, intervention, and the shifting balance of power in West Africa. France’s enduring influence, Nigeria’s assertive role, and the silence of Russia and China all reveal the complex geopolitics at play.

Benin’s crisis may be thousands of kilometers away, but its echoes reach Rotterdam’s streets, reminding us that history, power, and resilience are always closer than they seem.

Leave a comment