Rotterdam moves at a steady pace. The cranes along the Nieuwe Maas trace their ballet, bikes weave through morning light, and news flows faster than the wind off the North Sea. From this city of trade and tides, the story of France’s colonial history in Africa feels less like something far away and more like a current that still runs through daily life. Cocoa arrives in bulk. Oil flows across contracts. Energy depends on uranium mined in deserts you’ll never visit. And if you’ve ever stood by the Erasmus Bridge watching cargo ships slide past, you know that what happens in Africa doesn’t stay in Africa. It lands here, in Europe’s largest port, shaping choices about trade, migration, and what we think freedom really means.

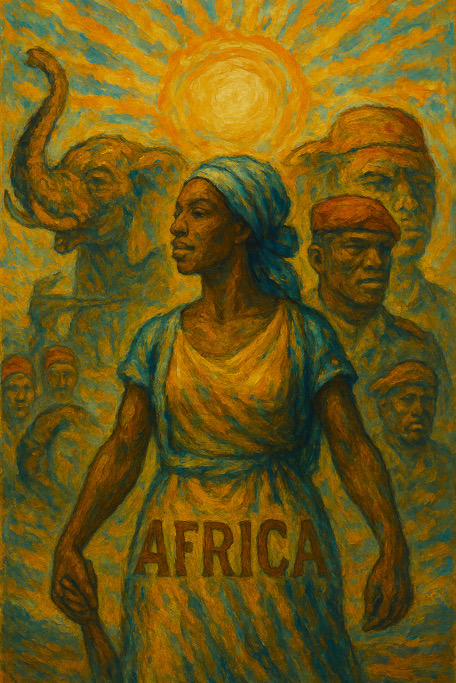

This story reaches back to a room in Berlin in the winter of 1884, snakes through battlefields and boardrooms, and stretches into speeches given today in Ouagadougou. It moves from maps drawn by men who never set foot in Timbuktu to alliances formed by leaders trying to rewrite a script that’s been handed down for a century and a half. It’s about France in Africa—how it came, how it stayed, and how it’s being challenged—ending with the voice of Ibrahim Traoré, a leader who insists the old arrangement has run its course.

Lines that cut across worlds

If there’s a single moment that leans heavily on everything that followed, it’s the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885. Diplomatic jackets, polished boots, and the certainty of men who believed they could draw futures with ink and rulers. No African voices in the room. France arrived already embedded in North Africa, with Algeria under settler control and influence stretching through Senegal. What it secured from that table was vast swathes of West and Central Africa: territories that would become Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Guinea, Chad, Gabon, the Central African Republic, and more.

Borders were etched without care for languages, trade patterns, herding routes, religions, or age-old pacts between communities. These lines pressed together groups who had little in common and split apart those who did, laying down future complications like landmines. The new order gave France routes, ports, and resources. It gave Africa an administrative code that measured lives by extractive logic.

Building an empire: conquest, code, and cash crops

French colonial power relied on a triangle that held tight: military conquest to secure control, administrative code to enforce it, and economic extraction to make it worthwhile.

Conquest was not a metaphor. In the Maghreb, resistance met artillery. In Morocco, the Rif War of the 1920s turned the mountains into a test site for brutal tactics. In West Africa, campaigns broke local sovereignties and forced chiefs into the chain. Once territory was subdued, administration arrived: the prefects, the code, the schools teaching the French language as a ticket to advancement. The ideology was assimilation—less partnership than conversion. If you spoke French, wore French suits, and memorized French books, you might be allowed closer to power, always with a hand on your shoulder reminding you who was still in charge.

Economically, the machine was efficient and relentless. Peanut fields in Senegal fed soap factories. Cotton from Upper Volta (later Burkina Faso) supplied mills. Cocoa from Côte d’Ivoire sweetened European tables. Coffee from Cameroon powered mornings. Over time, minerals joined the list: gold in Mali, bauxite in Guinea, uranium in Niger. Rail lines were laid not to connect African towns to each other for the sake of people, but to connect mines to ports for the sake of shipments. The shape of the economy pressed downward: you grow and dig, we process and profit.

Resistance, survival, and the politics of dignity

Empire invites resistance. It always has. Across French Africa, resistance took many forms: armed uprisings, tax boycotts, refusal to serve in colonial armies, print and poetry that insisted on dignity. Some fought to restore local authority; others imagined a future that wasn’t defined by European standards.

World War II changed the balance subtly but decisively. African soldiers fought and died for France, and the irony sharpened: why bleed for a land that still called you subject, not citizen? In the late 1940s and 1950s, the politics of independence matured. African intellectuals, trade unionists, and community leaders demanded the right to decide their own destinies.

The French state tried to shift the furniture while keeping the house: the Union Française, later the Communauté Française, offered a softer version of control. More local authority, but not full autonomy. In 1958, when a constitutional referendum offered association under Paris or a tough road to full independence, Guinea’s Sékou Touré famously chose the hard path, declaring, “We prefer freedom in poverty to riches in slavery.” France cut Guinea off within weeks. The lesson was clear: independence would not be gifted; it would be taken.

Independence: a calendar of exits and the weight of continuity

Between 1956 and 1962, the map changed quickly. Morocco and Tunisia gained independence in 1956. In 1960—the “Year of Africa”—West and Central African territories left the colonial frame one after another: Senegal, Mali (formerly French Sudan), Côte d’Ivoire, Benin (Dahomey), Niger, Burkina Faso (Upper Volta), Chad, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo (Brazzaville), the Central African Republic, Mauritania, and more. Madagascar had already taken its step; later, the Comoros and Djibouti would exit.

Algeria’s departure came last and bloodiest, after a war from 1954 to 1962 that tore hearts and households apart. Independence meant flags raised, anthems sung, embassies opened. But it also meant something more complicated: the skeleton of colonial administration remained inside the body. Borders were the same. The railway ran to the port, just as before. Contracts carried over. Economic ties felt less like bonds and more like chains.

The CFA franc: stability as a leash

Even as countries walked out of the colonial door, the money stayed French. The CFA franc—created in 1945—survived independence. Pegged first to the French franc, now to the euro, it offered predictability. Inflation didn’t spiral. Investors liked the arrangement. But predictability had a price. Control over monetary policy—devaluations, interest rates, currency reserves—sat in Paris-adjacent structures. Fourteen countries still use the CFA, across two zones in West and Central Africa.

For many, the CFA stands as the clearest symbol of incomplete independence. The argument is simple: when your budget depends on a currency controlled beyond your parliament and your central bank must maintain foreign reserves abroad, you are not steering your own economy. Supporters counter: the CFA prevents economic chaos and keeps trade stable. But when mining profits leave faster than jobs arrive, when farmers can’t buffer price shocks, stability feels like a whisper compared to sovereignty’s roar.

Françafrique: a network without a flag

Independence removed the flag but left the network. Françafrique is the name given to the web of interests and influence that connected Paris to African capitals long after colonial rule ended. It wasn’t written on treaties; it lived in habits, friendships, military cooperation, special contracts, and discreet visits.

French troops remained in places like Chad and Côte d’Ivoire, later Mali, often framed as partners in stability. French companies held big stakes in oil, gas, mining, and telecom. Political elites leaned toward Paris for diplomatic cover and financial support. When crises flared, intervention often followed. From the outside, this looked like partnership; from the inside, it often felt like supervision.

Françafrique’s logic outlasted presidents. But resentment grew. The generation born well after independence heard the word “partner” and asked why resources still moved outward while poverty remained stubbornly inside.

The Sahel grinds under new wars

The deserts and savannas of the Sahel carried calm and caravans for centuries. In recent decades, they’ve carried conflict. A complicated set of factors fueled the fire: the spillover of militants and weapons from Algeria’s civil conflict in the 1990s, the collapse of Libya in 2011, local feuds over land and grazing, weak state services in vast territories, and cross-border smuggling economies that rewarded armed groups.

Jihadist organizations linked to Al-Qaida and the Islamic State spread through Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. Towns were attacked, ambushes became common on highways, and millions fled their homes. France launched Operation Serval in 2013 to push militants out of northern Mali, then Operation Barkhane to patrol the wider Sahel. There were successes—territory retaken, leaders killed—but the root causes remained. Trust in foreign troops frayed. Communities felt caught between militants and soldiers; protection sometimes looked like occupation.

For Europe, this mattered instantly. Migration routes shifted. Aid budgets rose. Security cooperation became a staple of diplomatic language. For Rotterdam, the ripple appeared in quiet ways: a headline, a shipment delayed, a conversation in a café where someone wondered why a region so rich on paper remained poor in practice.

Resource wealth, local scarcity

Stand in Rotterdam’s Markthal under that painted arch of fruits and flowers and imagine the supply chains behind every bite. Côte d’Ivoire produces about 40% of the world’s cocoa. Burkina Faso grows cotton that threads through fashion. Mali’s gold moves into global vaults. Niger’s uranium powers a significant share of French electricity. Yet many communities at the source live with unreliable power, low pay, and few services.

The economics are straightforward and brutal: when value-added happens abroad, profits follow. If your country exports raw cocoa and imports expensive chocolate, the balance tilts against you. If your gold leaves as bullion and returns as jewelry priced far above the wage of a miner, sovereignty feels like a story, not a paycheck. Leaders have promised reform—renegotiating contracts, boosting local processing, capturing more tax revenue—but the task is steep when the global market has already decided where the margins live.

ECOWAS, the regional frame, and a split in the family

West Africa’s regional bloc, ECOWAS, has long aimed to coordinate economies, settle disputes, and ease movement. In recent years, it has also confronted coups, sanctions, and a deep debate about sovereignty. When military regimes took power in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger, ECOWAS pushed for quick transitions to civilian rule and threatened penalties. The response was defiant.

The split is about more than politics. It’s about the model of development and external alliances. Should West Africa anchor itself in older partnerships with France and the EU, or should it renegotiate everything, even if that means walking into isolation? The answer from the Sahel was the latter. A new group—politically aligned, security-focused—began to cohere.

The AES: a pact in the sand

In 2023, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger signed the Liptako-Gourma Charter, a mutual defense arrangement. In 2024, they formalized a broader confederation—the Alliance des États du Sahel (AES)—built on military cooperation, shared political goals, and an ambition to sync economic policies. The symbolism is loud: a joint stand against external pressure, a rejection of the old architecture, and a promise to build something more assertive.

It’s a bet on solidarity under hard conditions. Security forces coordinate. Borders are treated as shared front lines against jihadist groups. Talks about currency and resource management hint at deeper economic shifts. The AES brands itself as a reset, not a tweak.

But it also faces the pull of other powers. As France steps back, Russia steps in—providing military support, often tied to mining deals and media narratives that frame the AES as a frontline against “neo-colonialism.” The question becomes sharp: can a break from Paris avoid becoming a bond with Moscow? Sovereignty isn’t just about who leaves; it’s about who arrives and on what terms.

Rotterdam’s vantage point: practical, global, and honest

From Rotterdam, the view carries a mix of pragmatism and empathy. Trade insists on stability. Ports like predictability. Ships keep moving when rules are clear and roads are safe. But the Dutch memory also holds the complexity of colonial histories—Indonesia, Suriname—and the learning that follows: sovereignty must mean more than ceremonies. It has to travel through budgets, banks, fields, and factories.

When reading about the CFA franc, Françafrique, or the AES, the lens here is practical. Are people living safer? Are schools open? Does electricity reach villages that power the labor behind exports? Does a farmer get a fair price? Does a miner receive a wage that can feed a family without fear? These are not abstract questions; they point directly to whether the next decade brings resilience or repeats the last.

Migration: a signal of pressure, not a failure of people

Migration flows from West Africa to Europe are the visible edge of invisible forces: insecurity, climate stress, low wages, and the absence of trust in futures at home. Stricter border controls change routes; they don’t erase hope or necessity. If AES reforms deliver security and jobs, fewer will feel compelled to risk the desert and the sea. If the fixes remain in speeches, the pressure will continue.

In Rotterdam, conversations about migration often turn serious and measured. This city understands movement. It tracks arrivals not just with policy, but with the memory of families who moved and settled before. Hearing about upheaval in the Sahel becomes a prompt for careful thinking rather than quick judgments.

Ibrahim Traoré: a voice at the end of a long hallway

All of this history leads to a figure who has stepped into the spotlight with intent: Ibrahim Traoré, Burkina Faso’s leader since a 2022 coup. He speaks in straight lines. His public message threads Sankara’s legacy—self-reliance, local production, pride without pomp—through the present crisis. He calls out the CFA franc as a symbol of dependency. He rails against Françafrique. He argues that Burkina Faso must control its gold revenues, secure its land, and stop exporting wealth while importing poverty.

His speeches land because they sound like a response to a century of experience. They reject the soft vocabulary of influence and insist on clarity: independence must be material, not performative. That doesn’t erase the problems. Burkina Faso remains under pressure from jihadist violence. Parts of the country are hard to govern. Media and opposition face constraints typical of military rule. The economy still leans heavily on commodities and doesn’t produce enough jobs. The everyday reality is tense.

But Traoré’s posture—aligned with Mali and Niger under the AES—signals that a line has been drawn. He is saying no to what feels like an old script and yes to something riskier, more demanding, and possibly more rewarding if handled with care. He asks for time. He demands patience and faith. He frames sovereignty as a work-in-progress rather than a flag already planted.

For Rotterdam, the end of this story is not an ending but a junction. It asks for clear eyes. It asks people who watch ships slide into port to remember that every container holds a chain of relationships. It suggests that independence is not made in one year or broken by one contract, but stitched slowly through better deals, fairer wages, and the quiet dignity of services that arrive on time.

Traoré’s name will be written at the end of many articles about France and Africa in the coming years. It belongs there—both as a challenge to the past and as a test for the future. Whether he and the AES can convert declarations into structures that survive stress will determine whether this chapter becomes a turning point or another bold paragraph in a long book still being written.

In the meantime, Rotterdam keeps moving, the Maas keeps flowing, and the world keeps knocking at a port that understands, better than most, how stories from far away end up right here.

Leave a comment