Rotterdam has always been a city of arrivals. Ships docking, families settling, stories unfolding in the corners of Crooswijk, Delfshaven, and the Nieuwe Binnenweg. It’s a place where migration isn’t an abstract concept but a lived reality, visible in storefronts, in the languages that echo through the streets, and in the faces that carry histories far beyond the Maas.

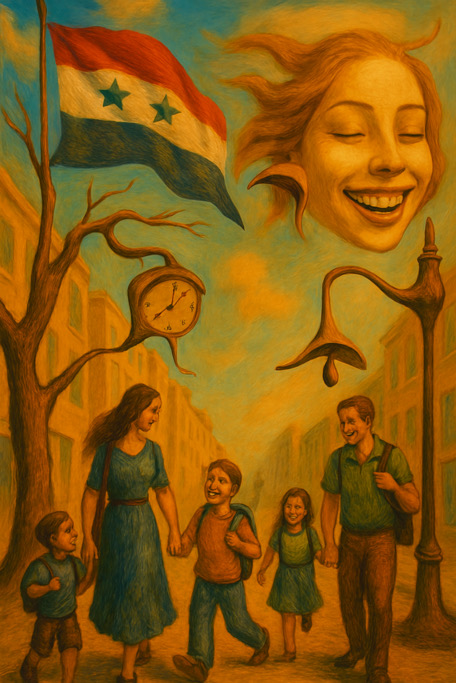

This December, the city witnessed something that felt both familiar and new: Syrians celebrating one year since the fall of Bashar al‑Assad’s regime. Flags waved, music spilled into the night, and car horns turned into a chorus of relief. For outsiders, it might have looked like just another street party. For those who know the weight of exile, it was something else entirely—a moment where trauma and hope collided in public view.

The Long Shadow of Assad

To understand why people danced in Rotterdam, you have to rewind decades. Assad wasn’t just another politician. His family ruled Syria for more than fifty years, first Hafez, then Bashar. Their regime was built on fear: prisons filled with dissidents, torture chambers hidden behind bureaucratic walls, and cities bombed into rubble during the civil war that erupted in 2011.

For Syrians in the Netherlands, many of whom fled during the height of that war, the fall of Assad was not just a headline. It was the collapse of a figure who had defined their nightmares. Even if the future of Syria remains uncertain, the symbolic weight of his departure is immense.

Rotterdam’s Syrian Story

The Syrian presence in Rotterdam didn’t begin with the Arab Spring. In the 1960s, Aramese Christians from Syria settled in Twente, building churches and communities. But the large wave that reshaped the city came after 2011. By 2015, during Europe’s refugee crisis, thousands of Syrians arrived in the Netherlands. Rotterdam, with its history of migration, became one of the places where they tried to rebuild.

Walk down the Crooswijkseweg and you’ll see it in small details: a shoarma shop taken over by new owners, the quiet determination in their eyes as they serve food to locals. For longtime residents, those eyes told stories of war—eyes that seemed to have “met the devil yesterday,” as one Rotterdammer put it. Trauma wasn’t hidden; it was visible in the way people carried themselves.

Comparing Waves of Migration

Rotterdam has seen this before. In the early 1990s, Somali refugees arrived, many scarred by civil war. Around the same time, Jewish asylum seekers from Russia found their way into Dutch hospitals and neighborhoods. Each group carried its own history, its own emotional imprint.

But the Syrian wave felt different. The sheer scale, the immediacy of the war broadcast on TV and social media, and the cultural contrasts made it impossible to ignore. For locals, it wasn’t just about new neighbors—it was about watching global conflict spill directly into their streets.

Freedom or Just the Fall?

The celebrations in Rotterdam raise a complicated question: are Syrians celebrating freedom, or simply the fall of a dictator? Freedom is a fragile word. Assad’s departure doesn’t automatically mean democracy, stability, or safety. Islamist groups like HTS, IS, and Al‑Qaeda have filled parts of the vacuum, each with their own strict codes and violent histories.

For many Syrians, though, the distinction doesn’t matter in that moment. The fall itself is worth celebrating. It’s the end of a regime that defined their suffering. Whether the future brings real freedom or new forms of oppression is a question for tomorrow. Today, the music and flags are about release.

The Dutch Lens: Stay or Go?

In the Netherlands, the conversation quickly shifts to another question: what now? Should Syrians return home now that Assad is gone? Many Dutch voices argue yes. The logic is simple: you fled war, the war is over, so go back.

But reality is more complex. Syria’s economy is shattered, institutions are chaotic, and safety is far from guaranteed. For many Syrians, returning would mean stepping back into uncertainty. Meanwhile, they have built lives here—children in Dutch schools, jobs in local businesses, friendships across communities.

The Dutch government knows this. With an aging population and a shrinking workforce, migration isn’t just tolerated; it’s quietly necessary. More workers mean more taxes, more stability for pensions, more hands in healthcare. Yet this pragmatic view clashes with the emotional reality in neighborhoods, where cultural differences can spark tension.

Division as a Tool

There’s another layer to this story: division itself. In Suriname, ethnic lines once kept communities apart, weakening collective resistance to power. In the Netherlands, verzuiling—Catholics, Protestants, liberals, socialists—played a similar role. People were divided into pillars, each with its own schools, newspapers, and clubs.

Today, migration adds new lines of division. Syrians, Somalis, Turks, Surinamers—all part of Rotterdam’s mosaic, but also sources of friction. For those in power, division can be useful. When communities clash, the government can step in as the “problem solver,” reinforcing its legitimacy. It’s a cycle as old as politics itself.

Trauma and Productivity

There’s a provocative idea circulating online: the most efficient populations are those shaped by trauma. After World War II, Europe rebuilt with extraordinary energy. The collective memory of destruction fueled innovation, solidarity, and growth.

Syrians carry their own trauma. For some, it becomes a drive to work harder, to build something new in safety. For others, it’s a burden that slows integration. Either way, the government sees potential. Encouraging mass return isn’t in its interest. Keeping Syrians here means more workers, more taxpayers, more resilience in the face of demographic decline.

Rotterdam’s Spirit

What makes Rotterdam unique is how it absorbs these global currents. The city doesn’t erase differences; it lives with them. Somali families in the 90s, Russian Jews in hospitals, Syrians running shoarma shops—each wave leaves a mark.

The Syrian celebration on the Nieuwe Binnenweg wasn’t just about Syria. It was about Rotterdam itself, a city that allows such moments to happen. A city where freedom is celebrated not in abstract speeches but in street parties, where trauma is visible but doesn’t silence joy.

The Bigger Picture

For readers outside the Netherlands, it’s important to see this not as a local curiosity but as part of a broader European story. Migration, trauma, division, and resilience are shaping the continent. Rotterdam is just one stage where these forces play out visibly.

The fall of Assad is a global event, but its echoes are felt in Dutch neighborhoods. The tension between staying and returning, between freedom and uncertainty, between division and solidarity—these are the questions that define not just Syrians, but the Dutch themselves.

Conclusion: Between Celebration and Uncertainty

So what now? Syrians in Rotterdam will keep celebrating, at least for now. Some may return if Syria stabilizes, but many will stay, weaving their stories into the fabric of the city. Dutch politics will continue its balancing act, caught between public sentiment and demographic necessity.

And Rotterdam will remain what it has always been: a city of arrivals, of contradictions, of resilience. A place where the fall of a dictator thousands of kilometers away can turn into a street party, and where the weight of history is carried in the eyes of those serving food on Crooswijkseweg.

In the end, the celebration isn’t just about Syria. It’s about the human need to mark endings, to find hope in collapse, and to claim joy even when the future is uncertain. Rotterdam understands that better than most.

Leave a comment